Meily de Leon, an FIU sophomore studying biology, is interested in plants. “Plants are big in healthcare – they’re in the medicine we take, the food we eat,” says the pre-med student. So interested, in fact, that after taking Javier Francisco-Ortega’s Biology II class last semester, she approached him and asked whether there were any opportunities available for her to work with plants in his lab at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, where he has an appointment as a Fairchild/FIU Molecular Plant Systematist.

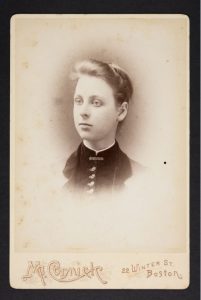

Francisco-Ortega is a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences. He has an interest in plant exploration, and was researching the history of collectors when he came across the name of Alice Carter Cook, a nineteenth-century botanist. Her name immediately stood out to Ortega, as the field of botany was dominated by men in the 1800s, and he began to do research.

What he found gripped him. Cook’s doctorate from Syracuse University in 1888 was groundbreaking – it was the first PhD in botany granted to a woman by any American university. She was also the one of the first women to get involved in botanical fieldwork, and was the among the first Americans to collect plants from the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago off the coast of northwestern Africa.

Dr. Ortega is himself from the Canary Islands. But more than that personal connection to Cook, he was inspired by what she had accomplished. “She took credit for her own work and published under her name. That might sound obvious to us today, but that was extraordinary for the time,” he says. He began a new project, intending to recreate and trace her steps, and catalogue and interpret her collections, in order to enhance her legacy. The project is being conducted in collaboration with Dr. Amelia Rodriguez, Dr. Isabel Francisco-Ortega, and Dr. Arnoldo Santos, who are recognized authorities in floristics and pre-Hispanic history of the Canary Islands. “I want to give her her rightful place in history,” Ortega says.

To do so, he hired de Leon, who was thrilled at the opportunity. On one hand, de Leon feels a kinship to Cook’s work in botany. “Plants are really interesting, and there’s so much more to them than people think. They have an amazing capability to change and alter depending on what’s going on around them,” she says. “And Cook is a truly fascinating, multi-faceted woman.” Cook’s specimens and field notes are in the Smithsonian, the world’s largest museum and research complex, and she also published anthropological studies.

Cook’s career also speaks to de Leon on a deeper level. “It’s really rare to see women in STEM fields in history, and I find her life and work inspiring,” she says. De Leon is aware that her goal of studying biology and becoming a doctor is possible in part to the efforts and contributions of women such as Cook. Just this week, she was one of the speakers at the 7th annual Women in Science Seminar, which brings together exceptional FIU women in the STEM fields who have pioneered major advancements within the community. The seminar provides an opportunity to discuss common struggles women face in male-dominated arenas. Speaking about both Cook’s accomplishments and the research project into her career, de Leon commented on how trailblazing Cook was, working during a time when women were not seen as the intellectual equals to men. “People say that the future is female,” she noted, “but I believe the past was female as well.”

When asked what one thing she would tell Cook if she could, de Leon thinks for a second. “I’d describe to her how different things are today. Women and minorities weren’t given the chances, but there’s been so much growth, thanks in part to women like her. I don’t think she’d ever imagined how far her work would impact people.”